Unless you’re living with your head buried in the sand, a completely understandable choice given the state of the world today, although not a wise plan if you truly want to live from the inside out (it’s part of citizenship), you likely heard a massive corporate freak out about the stock market dropping over the past week.

I get why, but I also think it creates an opportunity to reflect on how we as men should think about markets and how we might tap into the effects of testosterone on our psychology to help us move towards a system that prioritizes human thriving.

Why The Freakout?

Why can I assume you heard about the freakout? Because the people who own the media are also part of the limited classwho owns the vast majority of stocks.

As of January 2024, 10% of Americans owned 93% of the stock and the bottom 50% of Americans owned only 1% of the stocks. However, as we’ve covered in the past, the stock accumulating 10% of Americans has an oversized influence on everything that happens in America, from what is on the news to whether or not legislation passes to who gets elected. So when Trump’s erratic behavior around tariffs prompts the stock market to drop and they see their overall net worth drop, we’re all bound to hear about it.

That said, even if you have no connection to the stock market, there’s reason for concern.

Personally, the worry that’s been front and center is the investments my dad made throughout his career as that’s part of the money my mom will live on for her remaining days. A collapse in the market could also mean a collapse in her savings. However, unlike my parents in decades past (or me today if I was heavily vested in the market), she doesn’t have enough life remaining to think about what happens over the next 20 years. It’s not like she can ride this out.

That said, my mom isn’t the only senior out there; she’s the closest one to me. The immediate future of millions of Boomers is, at some level, tied to the stock market. A big enough drop will have tragic effects on their livelihood which in turn puts pressure on their children to help with their care.

The other reason for concern is that the way we do business and our understanding of economics in America is largely tied to the stock market. When the market goes down, so does the confidence of both businesses and consumers. People restrict unnecessary spending. The odds of layoffs increase.

Ultimately, this could get messy for all of us.

But why does something that so few people hold a significant investment in have so much sway over our economic well-being?

Why Is The Stock Market So Central

Whether you know the name or not, Milton Friedman, the leading voice for the Chicago School of Economics, holds an outsized influence in your life. In the economic chaos of the 1970s, Friedman offered a theory on how to fix things and it has guided our economic policy ever since.

What Happened in the 1970s?

After WW II the value of the US Dollar was tied to the value of gold and other currencies around the world were tied to the value of the US Dollar. However, the US’s attempt to simultaneously fight the Vietnam War and manifest LBJ’svisionary Great Society (which sought to end poverty and counter a history of racial injustice), led to massive budget deficits. This meant the country’s gold reserves could no longer support all the dollars in circulation. In response, President Nixon took the US off the gold standard prompting currencies around the world to fluctuate in value; fueling economic uncertainty and inflation.

Simultaneously, OPEC placed an oil embargo on nations that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War causing oil prices to quadruple. At the end of the decade, the Iranian Revolution disrupted supply chains causing another spike in gas prices.

The ’70s is also when American companies began offshoring manufacturing which started the collapse of blue-collar work in America.

As a result, the country experienced simultaneously high inflation and unemployment, also known as stagflation. Some commentators worry we might soon find ourselves in a similar state of economic precarity.

What Did Friedman Argue?

Into this chaos, Milton Friedman brought a form of the libertarian argument that markets are magical and if you get government out of the way through deregulation and tax cuts, then the system will naturally find a place of homeostasis.

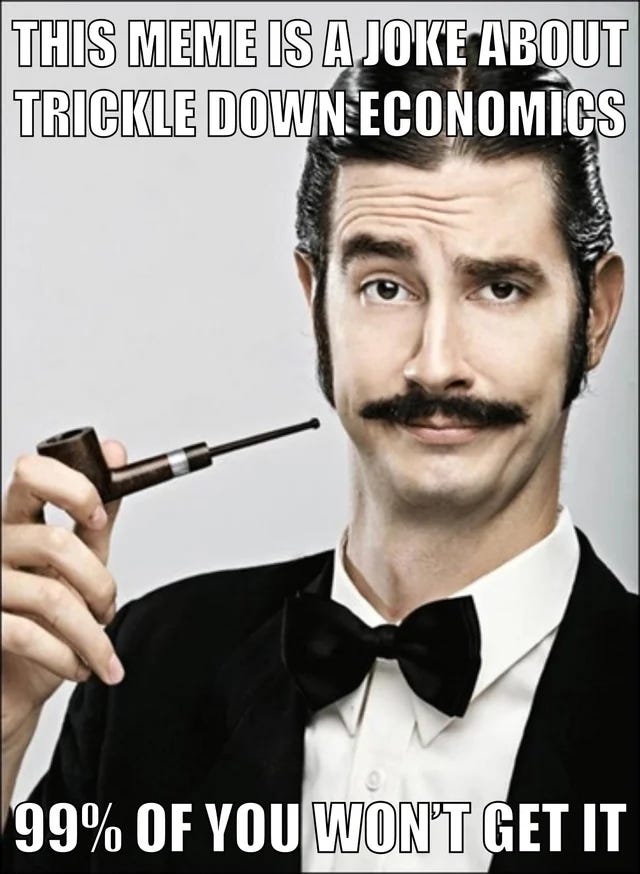

Friedman also popularized the idea of shareholder primacy, that is, the notion that a publicly traded corporation's only responsibility is maximizing profits for shareholders with Trickle-down Economics serving as the promised counterbalance to get the masses on board.

The idea gained such popularity that, in Delaware, where many US companies are incorporated, corporate law requires directors to act in the interests of the corporation and its shareholders. There is some space for discretionary consideration of the company's long-term success, care for employees, environmental impact, and other stakeholders.

It’s Not Just Friedman (or the 1970’s)

Now, I don’t want to put all the blame on Friedman, after all, the Industrial Revolution resulted in a massive concentration of corporate power, and much of the economic story of the 1900s is about the government trying to contain corporate power. Sometimes it was successful, and at other times it wasn’t.

For example, in 1919, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that a business corporation primarily exists for the benefit of its stockholders so while Henry Ford wanted to reinvest profits into wages and product improvements, he was legally forced to distribute dividends to the company’s shareholders.

Also, as a part of his policy recommendations, Friedman included a Negative Tax, a form of Universal Basic Income where, if you don’t reach a certain income threshold, instead of paying taxes, the government pays you half the difference between what you earn and a pre-set minimum. The idea was to make sure everyone had something to live on but to not disincentivize work. Obviously this Friedman policy wasn’t adopted while other aspects were.

Stocks Take Center Stage

Since the stock market sets shareholder value, and because shareholder value holds a space of primacy in our economic system, the stock market is the key metric for measuring our country’s economic health.

This system also holds a strong appeal for men. After all, testosterone makes us goal-directed, invites risk-taking, and fuels the pursuit of dominance. When we are told to do everything in our power to make sure that stock prices soar, it touches on everything that appeals to our biology and results in some rather creative “solutions” as we seek to financialize everything.

Take for example this 2023 overview of how we turned airlines into banks:

As another example, The Lever did an 8-part podcast series called Meltdown on the 2008 housing crisis, and the lengths companies went to in an effort to juice stock prices.

In a move that’s a bit less creative, in the last five years, corporations have spent over $6 trillion dollars in stock buybacks, a move that artificially pumps up stock prices and is done using money that could just as easily go to wages, research and development, or lower prices for consumers.

This heavy focus on financialization also explains the collapse of once great American companies like my once beloved Apple, and Southwest Airlines, whose stock market value you went up last week even as they announced that not only was open seating going away, but so is two bags fly free.

However, there are some significant problems with this approach.

What the Stock Market Doesn’t Measure

As the above examples demonstrate, a stock price can have very little to do with things like:

the well-being of a company's employees (a living wage, benefits, work-life balance, etc.)

the quality of a product a corporation makes

the environmental impact of production

It all reminds me of the clip from Pretty Woman when Edward (played by Richard Gere) tells his lawyer (played by Jason Alexander), “We don’t make anything.”

The lawyer replies, “We make money.”

Although, the real irony here is that there isn’t any actual money in the stock market, rather it’s all based on the speculative value of what a company is worth.

In other words, the thing that has such a significant impact on our lives is, at least at some level, an illusion (which in part explains why it’s so easy for Trump’s sporadic behavior to cause such chaos).

A More Worthy Pursuit

So what would a better system look like? What are goals we can strive for? What risks can we take to press for a better system that actually facilitates human thriving rather than one that helps the rich get richer and leaves the rest of us battling one another in a quest for survival?

I see two potential paths forward. One that seeks to change the system from the inside and another that creates something new on the outside that makes the current system obsolete.

From The Inside

As a worker, you have two sources of power in the market: your labor and your spending.

Corporations depend on both, and withholding one, the other, or both is one way to make demands. This might explain why, while it hasn’t received the same amount of attention as other DOGE actions, Elon has gone after the National Labor Relations Board and any other body that is designed to hold corporations accountable. It also explains why executives like this guy want to keep workers on edge:

As another option, since those of us in the United States still have elections, we have the opportunity to work from inside the system, not by voting Red or Blue as both Republicans and Democrats have committed themselves to the 10% who own all the stocks, but by advocating for other policies and the candidates who support them.

Some specific policies I look for:

Anti-trust policy increases competition which in turn requires companies to come to market with a better product or pay better wages. This is why there were so many hit pieces on Lina Kahn.

Get rid of non-compete agreements. These limit your ability to move from one company to another, which also means that companies can’t compete for your services. Ultimately, this decreases your ability to make more money. The Biden Administration outlawed these agreements but the Trump Administration brought them back on day one.

A Windfall Profits Tax would heavily tax excessive profits (the kinds used to do stock buybacks). This would incentivize higher wages and investments in research and development. For example, during the Eisenhower Administration, corporations were taxed 30% for the first $25,000 in profits and 52% for anything over that amount. Currently, the corporate tax rate sits at 21%, but there are so many loopholes that companies like Amazon are famous for not paying any taxes.

Exploitative immigration hurts labor on two fronts:

many corporations depend on undocumented workers for cheap labor and a workforce that has no grounds to protest inhumane working conditions

in the tech sector, H1B Visas bring highly skilled labor to the country and do so at reduced wages while binding the employee's residency to their employer making them far more pliable

Stakeholder capitalism where there are multiple bottom lines, including employees, customers, and the environment would definancialize the economy.

Getting corporate money out of politics and making elections publicly funded would mean that voters are once again the priority of elected officials.

Single-payer healthcare is another option, especially if we develop a system that prioritizes health over sickness management. This would save taxpayers money and be a boon to small businesses by eliminating healthcare from compensation packages, and a healthier workforce is a more productive workforce (although not as lucrative as the perpetually sick but not dead citizenry a for-profit healthcare system desires).

From The Outside

Another option is to build something new from the outside. While ideas on how to do this are somewhat new to me, I’m enjoying this Substack that explores the possibilities:

The Manliest Way To Approach Markets

The point is, half of the population is testosterone-fueled, and that doesn’t have to be a bad thing. It’s all about the goals we set, the risks we invite, and the values we want to establish. The real question is whether or not we have the courage to challenge the system.

Are you taking things on within, without, or both?